Understanding Warfeatured

I fear that we will see a big multicountry war in the next decade. This feeling could have arisen because of conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza and because of rising tensions between the big powers of the world. It could be because I have been reading a lot of history in the last year and because Covid has made it easier for us to think the unthinkable. Or it could be just a consequence of increasing pessimism that comes to many of us with age and weakening digestion. The feeling led me to try to understand war. I wanted to understand which factors determine the outcome in a war and whether we can predict who would win? This post is an exploration of these questions. Disclaimer: If you are a warrior or a scholar of war, you may find this post very basic.

A lot of my understanding comes from the excellent “Allure of Battle” by Cathal J. Nolan. The book is a journey through the wars of Europe over centuries and I highly recommend it.

The first thing that I understood about wars is that there is no wishing them away. Wars change society and they have happened frequently in the past.

Wars are consequential and frequent

Understanding war does not mean supporting it. We can all agree that wars are horrible. But we also need to acknowledge that they are consequential. As Nolan says,

‘… war remains hugely important in explaining much history and wider human affairs. Indeed, it may be the most important thing. Armed conflict is too important to be reduced to bromides that “war doesn’t solve anything.” War in history has in fact decided many truly important things…that war remains the most expensive, complex, physically and emotionally and morally demanding enterprise that humans collectively undertake.’

Not only are wars consequential, they happen depressingly frequently. Reading the book, I got the feeling that European history is one of war after another war. Each more devastating than the previous one. The occasional periods of peace only served to lull people. For example just before 1914,

‘Serious people said that war could never happen… Panglossian economists and editorialists wrote that war’s time was long past, that the world had entered a new era of integrated markets, historical material prosperity, remarkable scientific advances, social and even moral progress…Norman Angell’s The Great Illusion was an international bestseller from 1910 widely deemed profound and prophetic. He wrote that the economies of all the major powers were so intertwined that war would no longer profit any country, as it must interrupt trade.’

Yet, just four years later, we had a war so widespread and devastating that it is called World War I.

Initiators of the many wars often believed that they were starting a short war that they would win in a decisive battle. Reality did not always cooperate with their beliefs. But before we go there, let us first look at what is ‘winning’ in a battle?

What is winning a battle?

It is easy to say who won in a cricket match. Not in a battle. How would you keep score? Is the side who has possession of the battlefield the winner? Or is it the side which has lesser casualties?

Many battles were fought in the War of Spanish Succession. One of the more famous battles was fought at Malplaquet. The French army was retreating in the war as it fought a coalition of Danes, Dutch, English and many other nationalities. The French commander, Marshal Claude Louis Villars, hoped to induce the allies to attack him at a location of his choosing.

The allied army did attack the French and a furious battle ensued. Vilars himself was wounded in the fighting and had to be evacuated. Over the period of the battle, the higher number of allied soldiers and superior guns began to assert itself. The French made an orderly retreat. The allies had the field and their co-commander Duke of Marlborough claimed Malplaquet as his great victory. And yet, ‘an astonishing 24,000 Allied killed and wounded lay upon the field including Prince Eugene’, Marlborough’s co-commander. The French in contrast had only 11,000 casualties.

In response the Duke of Marlborough’s victory claims, Villers had this to say to his emperor Louis XIV,

“If God gives us the grace to lose another similar battle, your Majesty can count on his enemies being destroyed.”

Nolan believes that the heavy casualties in Malplaquet shocked the Dutch and British leadership. Their resolution to carry on fighting weakened. To them Malplaquet showed that France, although weak, had a lot of resilience left. Nolan has no doubt that the allies were defeated at Malplaquet.

In absence of score keeping, it is not easy to determine who has won a battle. Understanding war becomes more complicated because winning a battle often does not mean winning the war.

Winning the battle does not mean winning a war

Nolan argues that battles are rarely decisive, especially in long wars. History has many examples of generals who inflicted crushing defeat on their opponents in a battle but could not win the wider war.

A remarkable example of this phenomenon is Hannibal’s campaign. The Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca crossed the Alps and attacked the ancient Roman empire. He totally destroyed an entire Roman army in a battle at Cannae. Perhaps 70,000 were killed at the cost of 5,000 of his troops. Yet, even this huge battle defeat did not lead to a defeat in the war for the Romans. They realized that it was unwise to meet Hannibal in open battles and started relying on their fortified towns unless it was absolutely necessary. When he was challenged to a battle in his campaign of 15 years, Hannibal always won. Yet, he had no sustainable result. With a combination of superior logistics and supplies, blockading of Hannbal’s supplies, attack on Hannibal’s home base and strategic alliances and tactics of avoiding battle, the Romans wore out Hannibal’s army. He lost his first and final battle in defending his home from the eventual Roman counter attack.

A great example of winning the battle but not the war is the Battle of Borodino. The battle came after Napoleon’s Grande Armée had marched hundreds of miles in Russia having fought only one battle. This was because of a deliberate Russian strategy. The Russian army kept retreating while stripping the land of food and poisoning the water so that the French army would not have supplies. The French army was stretched on difficult roads and was attacked by Cossacks on its flanks and rear. Disease, starvation and desertion weakened the marching army. At Borodino, Napoleon had the possession of the field as the Russian army retreated in the night. The French army also had fewer dead than the Russians. Against the 45,000 Russian casualties, Napoleon lost 35,000. And yet, it can be said that the battle of Bordino was the beginning of the end of Napoleon. The Russian retreat was orderly which meant that there was no wholescale slaughter. The Russians could also replace their casualties much more easily than the French could. The French entered Moscow few days later. Most of the civilians had already left. Napoleon stayed overnight in the Tsar’s palace but woke up to the city burning. Saboteurs had set Moscow on fire to deny the invading army shelter. Napoleon’s army began its retreat in slightly more than thirty days.

Napoleon had entered Russia with 640,000 men in mid summer 1812. By the time he had reached to within 100 miles of Moscow, the army was reduced to 130,000 fighting fit men. Many men and animals were killed in the march because of lack of water and food and because of disease. When foragers from the French army tried to go deeper into Russian territory for food, they were harassed by Russian light cavalry. The French army also lost many men because of desertions. Of the 6,40,000 that crossed the Niemen river on the way in, fewer than 50,000 recrossed it in winter. Russians buried or burned 400,000 men left behind.

If winning battles is not as important as most people think, then what is? To understand this, let us build a grossly simplified model of a conflict. Keep in mind the aphorism that all models are wrong but some are useful.

A crude model of conflict

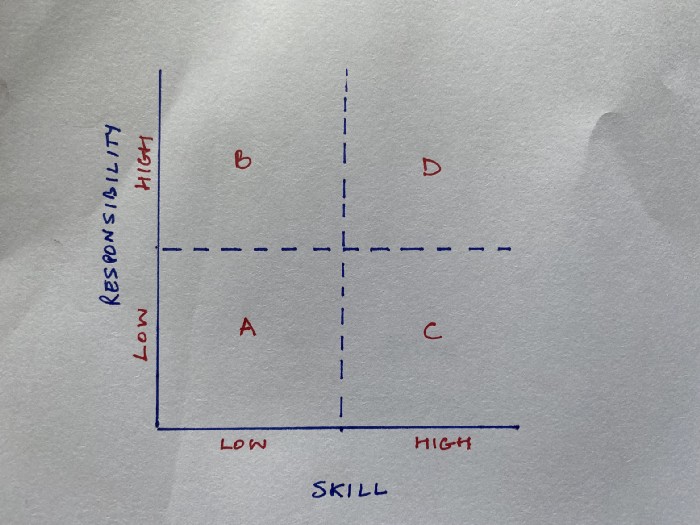

What will happen if ten armed men are fighting fifty other armed men? The correct answer is that ‘it depends.’ Here are some of the things that it depends on.

- What is the range and accuracy of the guns that the men have? If the range of the guns of the ten men is much longer than that of the guns of the second group, it is possible that the ten prevail if they manage to stay far enough away from the fifty.

- What is the age and training levels of the two teams? A smaller but younger and well trained team could beat a much larger but older and untrained force.

- What is the firing rate of the guns? If the ten men are fighting with automatics but the fifty are fighting with centuries old muskets, it is possible that the smaller team wins.

- What is the cover that the two teams have? Is the smaller team defending from behind heavily fortified structures and is the larger team attacking it? Can the defending team use natural barriers like mountains or rivers? If yes, the defending team could have a huge advantage.

- Can the attacking force concentrate its force to make a breakthrough in the defenses? The attacking force could then isolate and overwhelm the defenders.

- What are the motivation levels of the two teams? Is it that the smaller defending team is fighting for its life whereas the larger team is attacking because it has been told to?

- What is the supply support that the two teams have? A higher firing rate may cease to be an advantage if you run out of bullets. A good defensive position may not remain an advantage if you cannot get water, food and ammunition.

Already our model of micro battle has become very complex. The complexity comes from various combinations of the above factors. For example, the defending force may have very good cover but may not be anywhere as well trained as the attacking force. When we scale this battle, complexity increases exponentially.

One general principle of war however is that defense is much easier than offense.

Defence

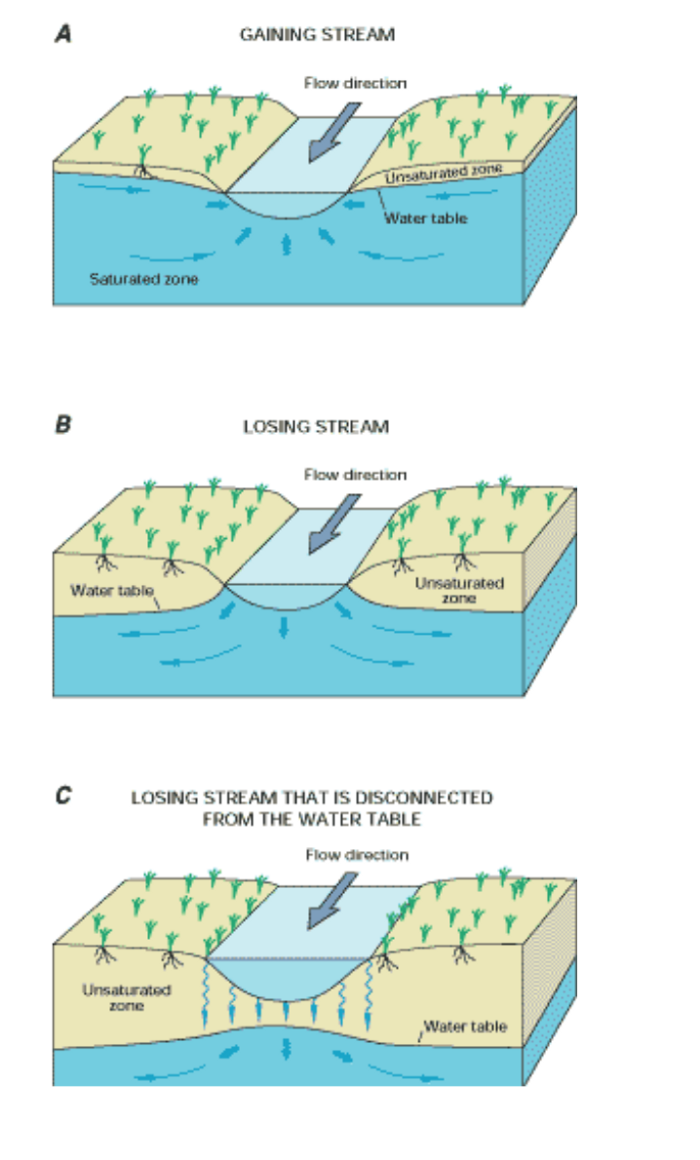

The Russians defended against Napoleon by retreating and by denying his army access to food. They would defend again more than hundred years later with Hitler’s army. Defense is what the allied army led by Duke of Wellington began with against Napoleon in Spain and Portugal. Romans did it against Hannibal centuries earlier. If not taken by surprise, a defending army will lose fewer men and lesser material as compared to an attacking army.

A defending army can choose the location for its defense. The geography may make it very difficult to attack. The defending army would build additional fortifications to make the attacking army’s work even tougher. These fortifications were literal fort walls centuries ago and now may be lines of underground trenches and bunkers supported by heavily mined areas. Last but not the least, the defending side is usually near its home and hence, its supply lines are much shorter.

Why attack?

The losses in battle of an attacking side are generally much higher than that of the defender. So why doesn’t everyone just defend? Well for one, the attacker can cut off a defender’s supply lines.

Why not defend? Starvation is a strong motivator

In medieval times, when defenders retreated behind thick walls, attackers would surround the fort to ensure that no food went in. Long sieges were not easy but if they were effectively implemented, the defending side would need to move out and offer battle. The attacking side could provide extra motivation for the defending side to venture out by indiscriminately attacking the civilian population outside the forts making it morally urgent for the ruler to venture out of the forts to defend his subjects.

This tactic of starvation and killing of civilian population did not die out in the middle ages. In World War II for example, both sides attacked each other’s supplies of food and fuel. As Nolan says

‘All the major belligerents in World War II returned to starvation as a major instrument of policy and of their war effort, whether by naval blockades or direct food confiscations.’

WWII also saw deliberate targeting of civilian populations to reduce the morale of the enemies. The atrocities of Germans in WWII are extensively documented but it was not that the other side was totally innocent (I am not drawing a moral equivalence here). As Nolan reports

‘Civilians were not killed as collateral damage in precision attacks that went awry, they were deliberately targeted in “morale bombings.” By the end of, Western Allied crews and policy destroyed 120 cities in Germany and 62 more in Japan, as firestorms reduced buildings and people to ash under incendiaries seeded by the air forces of the democratic nations.’

Even without starvation and ‘morale bombings’ one side or the other may be tempted to leave its well fortified positions at attack because an attritional conflict may become a question of who has more men and material and one side feels that it is at a disadvantage in the long run.

Why not defend? Attritional war is a war of men and material

Wars test supply and logistics in ways that peace times just cannot. Take ammunition. The rate of production of ammunition in peace times is not even a small fraction of what may be needed in war. Here is Nolan on World War I.

‘Fighting slowed in the first months of 1915 as artillery in all armies was retarded by an across-the-board shell shortage. Batteries started to hoard shells, as individual guns were reduced to just five or ten rounds per day, sometimes to just one, defeating the design and purpose of rapid-fire, self recoiling modern guns. Shell manufacturing during Prussia’s 19th century wars was 7,000 per week. By 1915 each army needed 20 times that production per day.’

The shells don’t just have to be manufactured, they have to be taken to the frontlines and distributed to individual guns spread over the front on a regular basis. All the while ensuring that you protect them from the enemy guns, planes and saboteurs who are trying to cut out your supply lines.

Your army may struggle with something as basic as fuel. This could be because countries that you thought were your friends refused to supply you with Oil. Or it could be because your enemy has blockaded your supplies as the United States did to Japan in World War II. Only 9% of Japanese tankers made it through US navy blockade in the last 15 months of World War II. That meant no fuel for the Japanese industry, the effect of which would cascade through to arms and ammunition.

Armies don’t just require ammunition. The men have to be fed and supplied with other necessities. Here is a small passage talking about the logistics of the French Front in WW I.

‘Behind the fighting lines the land was crisscrossed and traced with military roads and railways; with long earthworks, endless rows of pine barracks. Fortified canals; with bunkers, depots, tank park and cemeteries; with R&R camps and brothels. Everything was serviced by seaside docks and busy ports that brought men to fight, women to nurse, food and war material from all over the world. It took 100,000 cooks to feed upwards of two million men on the Western Front alone, every day, despite frontline troops eating cold food such as tinned bully beef, hard cheese and harder biscuits.’

War time shortage of material could be for something less obvious than food. Ed Conway writes about this in his book Material World. In World War I, Britain had a shortage of binoculars as the lens industry was predominantly based in Germany. Binoculars were needed by artillery men to improve the accuracy of their guns. Conway writes how Britain was able to place an order for binoculars with their enemy Germany, who was desperate for rubber. Britain controlled the supply of rubber.

Armies can run out of not only material but also men. By the end of his campaigns, Napoleon had run through all his veteran fighters and younger and younger boys were being drafted in his armies. The mortality rate for boys born between 1790 and 1795 was 38%!!

Fear of running out of men and material can be a reason for attacking. Another contributor can paradoxically be too much bravery, honor and initiative. Characteristics which are essential for fighting a war.

Elan must. But…

Germany sent many armies into France in the beginning of World War I. They hoped to swiftly annihilate the French armies so their men could dash to their Eastern front to face Russia. The battle near river Marne killed German hopes of a quick victory. The two sides then got into a stalemate of trench warfare. They faced each other in trenches that stretched to the Atlantic sea. Time was against the German side since the allies would outcompete the Germans on men and material. Falkenahyn, the man in charge of German forces, devised a plan to break this stalemate.

Falkenahyn hoped to provoke the French into an immense counterattack at a place of his choosing in Verdun. He hoped that his carefully placed artillery would obliterate the French counterattack. Furthermore, he hoped that the French would keep counter attacking because of the strategic importance of Verdun and prestige. Falkenhayn expected to finish a lot of French reserves in Verdun which would open gaps in French defensive lines elsewhere.

The plan did not work out as Falkenhayn expected. One of the big reasons was that the German generals in charge pushed their infantry to attack way beyond what was the strategic objective. Not only did this result in very high infantry losses for the German side, it also meant that when the French counterattacked, they did it beyond the range of the German artillery. The French also wasted many men in their counterattacks. This happened again and again. In the first five days, the French lost 24,000 men which would have been a success for the Germans except they lost 25,000. Over the entire ten month battle — the longest in history — the Germans lost 337,000 men as against 377,000 French.

This was a battle of attrition and a battle of logistics. ‘At the height of the effort, 6,000 trucks and cars arrived at the terminus every 24 hours, or one every 14 seconds. Discipline was ruthlessly enforced on a no-stops lifeline French called the Voie Sacree — the Holy Road.’

Nolan notes,

‘Falkenhayn wanted one thing: defensive bloodbath by artillery. His generals moved instead like moths to the flame of battle…The side that was better at logistics, won. The French were always going to be better at logistics and Falkenhayn knew that. His general had other ideas.’

Why did the German generals keep overcommitting their infantry? Because that was the German way. Attack was in the ‘fiber of German military thinking’ because it was a strategic necessity for a country that was surrounded by great powers and because it had worked in the past.

Why not defend? Because attack has been a necessity and has worked in the past

Prussia was a Germanic state that was surrounded by great powers. The mighty French on one side, the Russians on the other and the Habsburgs on the South. Prussians wanted to become great powers themselves. For this, they needed to increase the territory and population under their control. The German unification wars were fought with this political aim.The Germans beat the Danes, the Austrians and the French in three wars in a less than ten year period. In each war, the Germans attacked with the aim of winning quick wars. This was so that other great powers did not get the time to intervene. They won, most spectacularly against the Habsburgs, but it is worth examining how much it took to win.

A lot needs to go right for a win including luck

Prussia attacked the Austrio Hungarian empire as it wished to take the German territories of the empire. The Prussian army had many advantages over its opponent and one of the chief ones was that its infantry was armed with Dreyse needle guns. The Austrio Hungarian infantry was armed with Lorenz rifled muskets. The needle guns were breech loading whereas the Lorenz rifles were muzzle loading.

A muzzle loaded gun is loaded with gun powder and ball through the end of the barrel from where the ball would come out. The ball needs to be pushed into the gun, typically using a ram rod. This process takes time as this video shows. Not only is the process slower, but also it requires the soldier to stand up. A breech loader in contrast is loaded from the back of the gun. This process is faster which means that the firing rate is higher. The gun also can be reloaded by soldiers who are prone. This would be a huge advantage for defenders. The range of the needle guns was also superior to the Lorenz rifles.

The needle guns were not a surprise for the Austrian as they had allied with Prussians just a few years ago in Denmark. Austrian officers had seen the superiority of Dreyse needle guns. So why did the Austrian armies not shift to breech loaders?

One reason was that Austria was near bankruptcy and Prussia was booming. Austria did not have the money to invest in new guns for its infantry and it did not have money to spend on the extra ammunition required for training as well as the war. Furthermore, Senior Austrian military officers did not trust their soldiers to not panic and use up all the ammunition very early in the fight, if they were given weapons that had a higher firing rate.

It was not just the Dreyse guns that allowed Prussia to beat Austria. Its mobilization was much better thanks to its investment in the then modern railway and telegraph technologies. Additionally, the Austrian commander was incompetent and chose the worst place to give battle in the battle of Königgrätz. The Austrian officers employed outdated tactics — tactics that had worked when the ranges of infantry weapons were much lower. Because of these tactics, elements of the Austrian army “Fought bravely, even recklessly but mostly uselessly.”

In spite of all these advantages, there was a time in the battle that the Prussians were in serious danger of losing. Partially it was because of Austrian artillery guns which were better. But a big reason was the Prussian need to finish wars fast. The famed commander of their army — Moltke — had attacked early. He hoped that one of his armies still on the march would join in time. Moltke’s second army came in just in time.

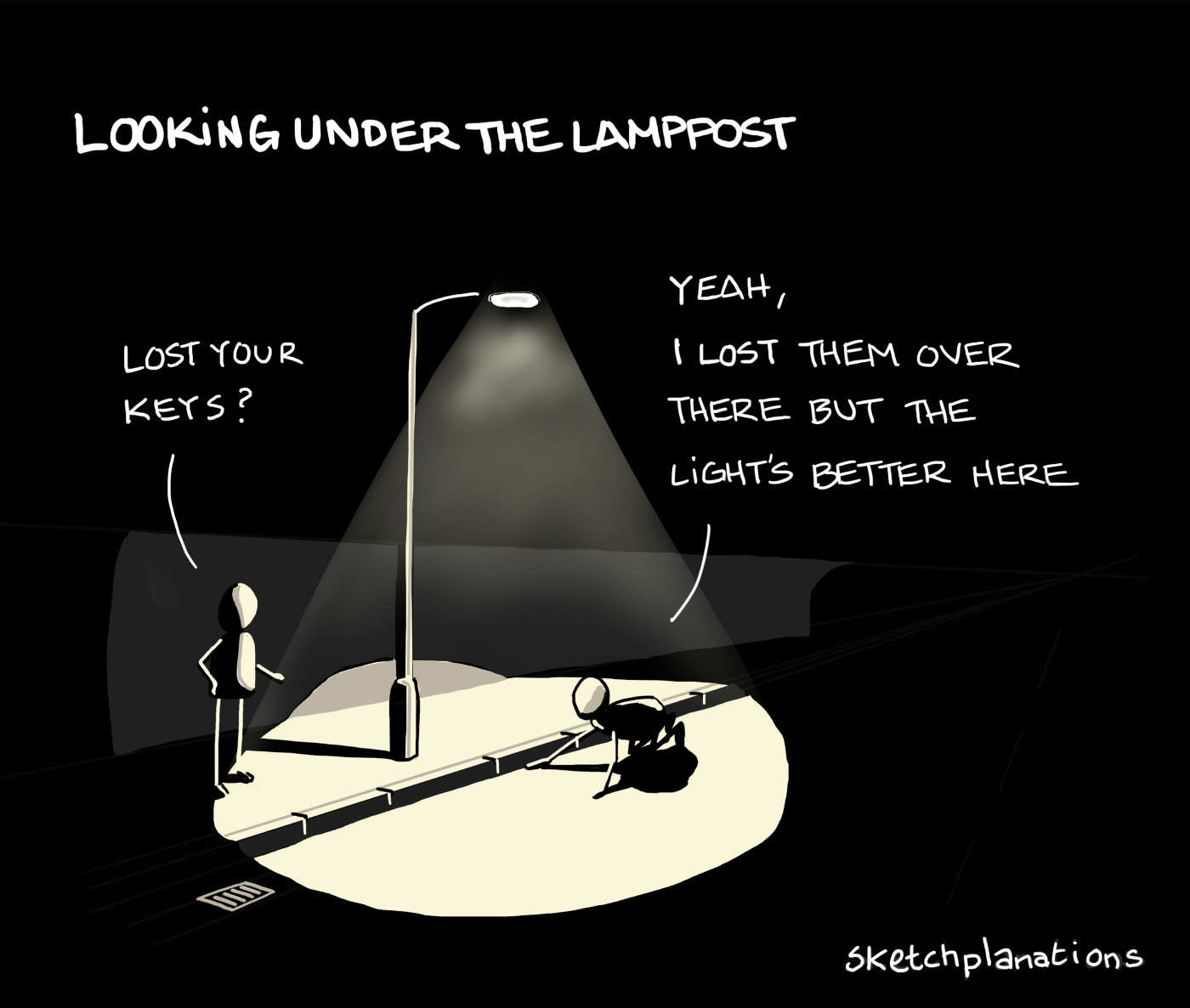

To quickly recap — the Prussians had the advantage of better weapons, tactics and leadership and still could have lost. That is the nature of battle. The Prussians had a much tougher time in France a few years later where they won, not in a quick battle but in an attritional siege. They forgot all this and believed that seeking and winning quick battles was the only way to fight war. But that is not all they forgot and this had consequences in the wars that followed.

They forgot that perhaps the biggest contribution to the unification war was not even in the war but in diplomacy and politics. Bismarck’s isolation of Habsburgs before the war helped ensure that no major power intervened in the war. His diplomacy after the war was even more important.

‘He blocked excessive demand by a usually cautious King Wilhelm I, who was suddenly avaricious for annexations. Bismarck insisted on no annexations of Austrian provinces, for that was likely to provoke France and Russia. Instead, he moderated the armistice to dissuade other powers from propping up Austria or trying to reverse the meaning within Germany of the decision won at Königgrätz.’

A country that keeps winning is very likely to create a coalition of embittered losers and fearful potential rivals. Eventually a large coalition will beat you with men and material even if you are a genius at waging war. A country using war as an instrument of politics should be clear about what its political goals are. In other words, do you know why you are fighting and when you have had enough?

A question that Napoleon never asked, it seems.

What did the “God of war” leave behind?

Clasuwitch, the famous German war theoretician, called Napoleon the God of war. Napoleon won countless battles. He was very gifted at tactical and operational level. His armies would routinely catch their enemies by surprise because of Napoleon’s genius at understanding the terrain, his enemies and at getting his armies to maneuver to be at the right time at the right place. Napoleon became the emperor in 1804. At his peak Napoleon ‘was the master of Europe from the Vistula to the channel’. But in a few short years, he had been exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in 1815. Why did the “God of War” and master of half of Europe end up as a prisoner on an island?

Clearly there were many factors that led to Napoleon’s downfall. The initial advantage that France had of levee en masse or conscription, which gave it huge armies, was copied by others. His enemies understood and countered his battlefield tactics. As time passed, Napoleon lost more and more of his veteran fighters. Britain’s sea blockade made a difference as did its twenty three year financing of Napoleon’s enemies. Napoleon’s campaigns in Russia and Spain dealt severe blows to his armies and his reputation for invincibility. And then all his enemies attacked him together. All these reasons are true and historians would doubtlessly point out many more that I have missed. But underlying these reasons is the main problem.

Napoleon did not wage war because he was trying to achieve an underlying political aim. He waged war for la glorie. It was one war after another as he could never get enough glory. He went into Russia without consolidating his victories in Spain and he had to pull out many of his veterans from Spain to accompany him in Russia. In Russia, when the enemy kept refusing him battle, he kept chasing them for hundreds of miles even as his supply lines stretched thinner and thinner and his men died of disease. His refusal to negotiate and his tendency to break treaties whenever he did enter them meant that all his enemies allied against him. Napoleon lost because he kept chasing the glory of winning the next battle. As Nolan said,

‘He should have been content to rule in peace. He never was.’

What wins wars and can we predict who will win?

Let us summarize what we have learnt

- It is not easy to determine who is the winner in a battle.

- The winner of a battle is not necessarily the winner in a war. Winning battles may tempt countries to fight even more battles.

- If a war becomes attritional, as it often does, then the country that can provide more men and material will prevail most of the time.

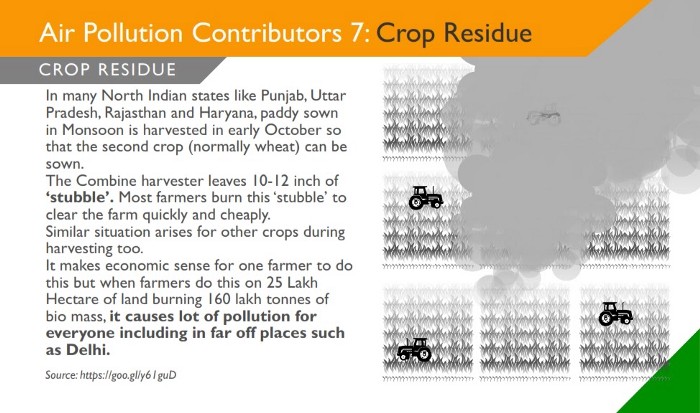

- War time logistics is an immense task. The country would need not only food and fuel but also other critical material. In today’s complex world, the list of such material could be very long. The manufacturing capacity of a country and its self reliance could be key.

- Defense is easier than offense. Countries may choose to attack instead of defending in order to achieve their political aims. Or they may do it because blockades are choking the supply of vital material. Or they may do it because of a culture of honor.

- Clarity of politics behind battles is extremely important. This clarity would help a country to know when to stop and to reduce the strength of coalitions against you.

War is complex. Predicting what will happen in a war between matched opponents is not easy. Being confident of those predictions is downright foolish. Recent events in Ukraine have demonstrated this again. Repeated predictions of an early Ukrainian (or Russian) victory by experts have not come true. It may be better to listen to cautious voices like that of Gray Connelly, who has been emphasizing the importance of the Russian capacity to generate men and material right from the beginning.

We cannot be sure what will happen in a war. Except that there would be death. If there is a war, there will be death.

War and death

The impression I got reading The Allure of Battle is that Nolan is antiwar but is pessimistic that humanity can avoid wars for long periods of time. The book has evocative passages throughout about the horrors that wars visit on us. I end with a particularly powerful passage.

‘What met a generation of schoolboys raised on heroic stories of Marlborough, Frederick and Napoleon was not glory but hard death in ways old and new. Cold death from a sniper while tangled and frantic on jags of barbed wire invented by far off ranchers to hem in cattle. Hot death as liquid flame gushed over a man to light him up like a Roman candle. Slick greasy death as a sawtooth bayonet snicked easily into a gut. Gurgling death, throat ripped out or a jaw torn away by a machine-gun bullet, unable to cry for aid. Lonely death at the bottom of a shallow crater filled with yellow rainwater and piss, and bits of horse and human flesh upturned and minced by the last bombardment. Instant death as a boy turned into a mush of pink pulp and red mist when a high-explosive shell landed a foot away, one drop in a steel rain that fell for days and night on end. Fumbling death from Mustard gas or worse, much worse chemicals as the war went on. So much death that tens of millions gagged down every meal inside a sweet-sick order of putrefying horse and human flesh.’

Liked what you read? Follow me on medium and choose the option to get the stories delivered to your Inbox.

You can follow AskHow India (@AskHowIndia) or me (@YogeshUpadh) on twitter or on LinkedIn

Telegram channel: t.me/YogeshUpadhyaya