The proposed UP population law will not achieve its aim but it is not easy to dismiss underlying concernsfeatured

The government of Uttar Pradesh (UP) has proposed a new law to ‘stabilize’ the population of the state by providing ‘incentives and disincentive’. Many commentators have alleged that the law has been proposed to drive a wedge between Hindus and Muslims. They further imply that that the demographic anxiety of Hindus is misplaced. I believe that there are surer ways of reducing fertility than this law, if that is indeed the aim. However, I would not be too quick to dismiss the demographic anxiety as irrational.

Representational Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

The proposed law has a long list of incentives for a couple with two children or less and another long list of disincentives for couples who have a third child. In my view, these incentives target a very small section of the population and more importantly, many of them are difficult to implement. Are there better options?

Let us start by looking at what is happening to fertility in India and UP.

India as a whole is already near replacement level of fertility

The Sample Registration System (SRS) found that in 2017, the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of India was 2.2. The replacement fertility rate is generally considered to be 2.1. Some scholars believe that given the low Sex Ratio at Birth in the country, even a total fertility rate of 2.2 may be replacement rate. In any case, the country is at or near the replacement rate fertility. The TFR in UP is higher than the national average. In 2017, it was 3.0. But it has been reducing for the last few decades. Will it come down further? If yes, how?

As I have covered in this piece, fertility depends a lot on childhood mortality. A sharp fall in fertility happens when couples know that their children have a high likelihood of survival. Additional falls in fertility happen with factors like urbanization and women’s education. If UP is concerned about population growth, then it should focus on maternal and child health. And it should focus on urbanization and women’s education and empowerment. These are sure ways of reducing future population growth.

I must note here that the population growth in a society continues till long after the fertility has reached replacement rate. This is because most of the people in such a society are young. As they marry and have their 2.1 children, the number of births in that society are way more than the number of deaths as the aged people group is much smaller. I have explained this topic here. The population of UP is expected to increase for many decades even as its fertility falls and the law cannot change that.

But what about the subtext, you ask? Many people have suggested that the proposed law in Uttar Pradesh has less to do with overall population growth and more to do with growth in Muslim population. Let us take a look at the issue next.

Islam and population growth in India

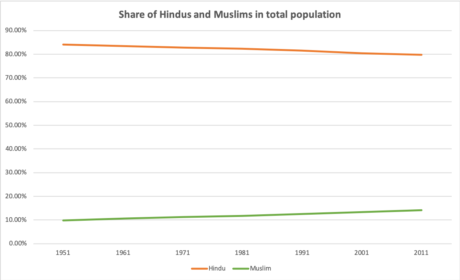

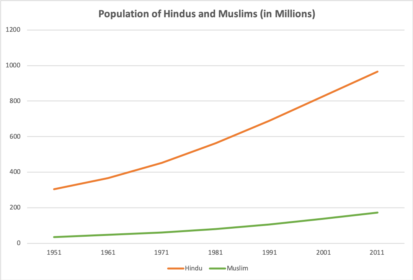

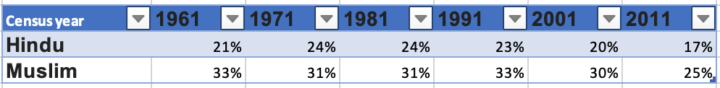

My piece on this topic was one of the most read posts that I have written. I began with these two charts.

As these charts show, the share of Muslim population in India has grown since independence. This is because the growth rate of Muslims is higher than that of non-Muslims. The table below gives the decadal growth rates.

However, the charts show that there is no chance of India becoming a Muslim majority country. Especially as the growth rate for both communities is reducing.

Moreover, data also shows that there is nothing inherently in Islam that leads to a very high rate of growth of population. Many Islamic countries have a low fertility. For example, the Islamic Republic of Iran had a fertility rate of 2.1 in 2017 as did Bangladesh. Even in Pakistan and Afghanistan the fertility has fallen sharply. The fertility in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir was 1.6 in 2017. It should be remembered that the population in J&K is majority Muslim. Sharp reduction in fertility happens in Islamic societies with sharp fall in childhood mortality and with increase in urbanization and women’s education and empowerment. Just like it happens in non-Islamic societies.

If there is no chance of Muslims becoming more than 50% of population of the country, why is there a fear in many circles of increase in share of Muslims? If the critics of the UP law are correct, the law has been probably been proposed to exploit this fear. Is this fear baseless?

Not so fast.

Democracy and demography

People vote on the basis of their identity. Not everyone but many people.

Identity is a complex thing but in our country two identities that are strongly associated with political preferences are caste and religion. Very crudely speaking, in many states, one side emphasizes the caste identity and the other stresses on the religious identity. In a few parts of the country — Mumbai and Delhi for example — the regional identity also becomes important. An increase in the share of population of any of these identities is concerning for people of the other identities and legitimately so. The number of votes win an identity power. And with power comes jobs, benefit and prestige.

Incidentally, identity is not just important in Indian democracy. Here is the then presidential candidate of United States, Joe Biden of Unites States saying that “If you have a problem figuring out whether you are for me or Trump, you ain’t black.” Politicians across the world emphasize identity because it works.

The exemplar of the importance of identity in India would be Assam. The demographic history of Assam is very complex. For the purposes of our discussion here, we can say that three voting blocks have tussled in Assam over the last many decades. They are the non-tribal native Assamese, Bengali speaking Muslims and Bengali speaking Hindus. The Bengalis speaking Muslims and Hindus migrated to the state over the last hundred and fifty years. Migrants and their descendants probably comprise more than 50% of the population of the state now. The state has seen many identity coalitions over the past decades. For example, at one time, the native Assamese were in coalition with Bengali speaking Muslims but they then got alarmed by a sharp increase in the number of Bengali Muslim voters

The share of Muslim population in Assam has steadily increased from 24% in 1971 to 34% in 2011. Many constituencies have become Muslim majority. There is dispute about whether immigration or higher fertility of Muslims is the cause of this change but there is no doubt in that this demographic change impacts power dynamics. To understand this issue more, you could read this compact piece.

Religion based demographic changes are not the only ones that lead to shift in power. Differences in fertility across regions can also change power dynamics. Northern states — with their higher fertility — have a higher share of population today than they did fifty years ago. However, their share of political power has stayed the same. Uttar Pradesh elects 80 Members of Parliament and Tamil Nadu elects 39 as they did in 1977. This is when the population of UP (231 million) has increased much more than the population of TN (71 million). Remember, each MP has an equal say in electing the Prime Minister of the country. I am sure that in my life time, people of UP (and other North Indian states) will agitate for a more equitable share of power and people from TN (and other Southern and Western states) will oppose it claiming that they’re being penalized for becoming more prosperous faster.

Here is the problem in a nutshell. Some identities have higher growth rates — many times because they are poorer. This higher growth rate leads to more votes and hence power in the hands of those identities. This is almost inevitable in a democracy.

This is a complex problem with no easy fixes. However, we also know that decline in fertility inevitably follows fall in child mortality which in turn depends on prosperity. If you are an Indian and are worried about the high fertility in another religion or region, then you should at least be supporting measures that lead to prosperity of that religion or region.

Author –

Yogesh Upadhyaya

(Yogesh Upadhyaya is one of the founders of AskHow India. Blogs are personal views.)

You can follow AskHow India (@AskHowIndia) or me (@Uppi89) on twitter or me on LinkedIn or Medium. DM me if you wish me to put you on WhatsApp distribution list.

How is China so welcoming of businesses? (REODB 2)featured

Chinese bureaucracy is very helpful to businesses. I met around fifty business leaders across India and this was one of the themes that came up often in our conversations. In the minds of many of these business leaders, there was no comparing the genuinely helpful Chinese bureaucracy and their India counterparts. Chinese government officials wooed you if you expressed an interest in investing in their area whereas the Indian bureaucracy was an obstacle that had to be circumvented. I tried to figure out why there is such a big difference in the attitude of the bureaucracy in the two countries. One crucial thing that I discovered was that the incentives — of local governments, of rank-and-file bureaucrats and of political leadership — are very different in China and in India.

Representational Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

Most times, people do what they are incentivized to do. This is true for organizations and it is true for individuals working in those organizations. Take sports for example. If the coach and players are judged by the team results and not individual performances, then the team will win more often. However, if the individual achievements of the players are celebrated more than team results, then the team would not win as much even as the players keep racking up personal achievements. What is true for sports teams is true for most organizations including governments. The incentives for government departments as well as for individual officers in China are aligned with growth of businesses. In India it is not so.

I have looked at incentives at three levels — Organizational, rank and file officers and senior leadership. For understanding the situation in China, I have relied on the excellent book -China’s Gilded Age by Yuen Yuen Ang. I have focused on the manufacturing sector because that is where India has really underperformed whereas China is the world leader.

Let us begin by looking at local governments.

Local government incentives

In my first post on Real Ease of Doing Business (REODB), I had detailed how local politicians and bureaucrats in India torment businesses. Of the many insightful comments that I got, this one from Yogesh Karnik is very relevant here.

“…In order to make it attractive, there needs to be revenue sharing with local bodies for the produce. That is, from tax revenue, a minute fraction should come back to local authorities for development of local area- say schools, road, water etc anything that locals would like to improve. This may act as incentive for allowing ease of business.” (Mildly edited for clarity),

In India a business pays very little money in taxes to the local governments. If a manufacturer were to put up a factory in a village, the gram panchayat would practically get nothing, at least officially in terms of taxes. The taxes or levies that an urban business may pay to a municipal body are also miniscule. The revenues of the local government do not increase materially if the businesses in their area do well.

This is true at the State Government level also. The Goods and Services Tax (GST) is charged on consumption of the good (or service) and no portion of it goes to the state where the goods were produced. The situation earlier was different.

Before the Goods and Services Tax (GST) became the law, we had Excise duty (tax on manufacturing) and Sales Tax. Excise duty was paid to the Central Government. The Sales Tax went to the State Government if the sale was in the same state as where the product was manufactured. If the sale was outside the state, then a Central Sales Tax (CST) was payable. This CST was transferred to the government of the state where the manufacturing was carried out. So, if a packet of biscuits was made in Gujarat and sold in Maharashtra, the CST collected would go to the state of Gujarat. Today, the GST would be split between the central government and the state of Maharashtra.

In short, the local and state governments make very little direct revenue from businesses set up in their area. Of course, a business would employ people who would consume goods and services and the state would get half of the GST on this consumption. However, this link is indirect.

Do Local governments in China get any revenue from businesses? Here is Ang

‘In China, local governments are not authorized to create their own taxes, but they are allowed to retain a certain portion of tax revenues according to tax sharing rules.’ (Emphasis added)

If the businesses do well, the tax revenues of the local body increases. This creates a powerful motivation for the local bodies to foster businesses. Note that for the local body, keeping a share of the tax revenue is different from getting a grant which might be funded from the overall tax revenues. In India, local bodies get grants. The share of the grant that goes to a local body would be based on conditions that have nothing to do with how businesses in their area are doing. If businesses in their area do well, the taxes of the local bodies in India do not increase.

In China, not only does the local government get to keep a share of the tax revenue, but also, the compensation of the lower-level bureaucracy depends on tax and other revenues of the department. Let us look at that next.

Does the rank-and-file bureaucracy benefit from being business friendly?

One of the most remarkable learnings I had about China is that a government department is allowed to distribute a part of its revenues to its employees. Here is Ang

‘In China allowances and perks are pegged to two sources of income: local tax revenues and the fees and fines extracted by individual agencies.’

So, if businesses do well, the incomes of the employees of local government increases. This phenomenon of employees getting a part of revenue of the department / government can create very significant differences in income. As Ang says,

‘Public employees in different localities, even ones that are geographically adjacent, may receive starkly unequal levels of remuneration. Within each locality, staff benefits also vary across departments.’

And,

‘Formal wages varied little across the counties, reflecting the fact that formal public salaries are standardized. By contrast, regional variance in fringe compensation is much wider,…In 2005, they ranged from as low as 4,752 Yuan to as high as 125,454 Yuan- a 26-fold difference!’

As one government official is quoted as saying,

“Our compensation is only about half that of bureaucrats in adjacent county Y. Our formal salary is the same, but the difference lies in subsidies and allowances, which is paid according to local tax revenues. County Y offers their staff a transportation subsidy and extra bonuses for achieving targets, but not our county. Why the big difference among counties? Our county is poor.”

This difference in incomes can create a powerful motivation for the bureaucracy to be business friendly. If businesses flourish in their jurisdiction, they make more money. This creates a strong competition between counties and provinces to attract businesses and to make sure that they do well.

Now, tax revenues are not the only source of revenues for local bodies and departments. They also get to retain the fees and fines that they impose on a business. This means that there is danger of bureaucrats harassing businesses by imposing a lot of fines to increase the department revenue and ultimately increase their own compensation. This reminds me of the story of the goose that lay golden eggs. The farmer couple who had the goose were not satisfied with the one golden egg a day and killed it to get the eggs all at once. Tragically, for both the gooses and its owners, they got nothing. Why don’t the Chinese rank and file bureaucracy kill businesses with fines and fees?

China has formal and informal systems to keep this tendency of lower bureaucrats in check. The political leadership realizes this danger and cracks down if the lower bureaucracy harasses the businesses too much. In addition to these systems, China has managed to create a culture where the bureaucracy fosters rather than hinders business. Or more eloquently acts as “helping hands’ rather than “grabbing hands”. As Ang says,

‘What distinguishes China is that even street-level bureaucrats know that they have a personal financial stake in economic performance, and curbing extraction today will benefit them over the long term.’

Here is a quote from a government official,

“If the overall economy prospers, then our departments will also benefit. Conversely, if each department only thinks about organizing or extracting revenues for itself, then, if our enterprises cannot survive, they will leave. Our local economy will be finished. Consequently, each department’s finances will worsen. This will turn into a vicious cycle. Only when we all work together can we promote local economic development. In the long term, only this strategy will benefit every department.”

The deputy mayor in staff meeting in Fujian province,

“Do not forget the fact that taxes paid by our enterprises are closely and personally connected to your benefit. Taxes collected go toward paying your allowances. So, serve your enterprises well.”

And this from a leadership slogan in a county of Hubei

“Investors are Gods, prospectors of investors are heroes, bureaucrats are humble servants, and those who harm corporate interests are sinners.”

Can you imagine any government official or politician saying any of this in India?

In India, the financial compensation of a government employee has no relationship with the tax revenues generated from their jurisdiction. Additionally, government officers would rarely be penalized if businesses in their area feel unwelcome. In fact, they would face adverse scrutiny if an audit reveals that they are in violation of any regulation or procedure. Thus, a government officer is incentivized to make sure the business enterprise follows each and every regulation. If the regulations are ill defined, contradictory or impractical, as they often are, then it is the problem of the business. The business can solve this problem by paying a small or not so small bribe. The government officers are incentivized to be at best be apathetic. Too many times they become “grabbing hands.”

It could be argued that even in the face of these incentives, a government officer should do the right thing. And many do. There are government officers who take risks with their careers to be business friendly because they believe that businesses generate employment and make their communities more prosperous. But in general, such officers are exceptions.

Can the political leadership change the attitude of bureaucracy? Let us look at their incentives next.

Does the political leadership in China benefit from being business friendly?

In one of my most read posts, I had argued that a Member of Parliament (MP) in India has very little incentive to work on job creation. First, most of the work of a MP is invisible to his voters. For example, if the MP works with the central government to increase tourism in his constituency, most of his voters will not be aware of what he did. Secondly, the best place for jobs may be outside the constituency. For example, development of an industrial park in a port may attract more businesses and create many more jobs than similar park in a hinterland district. But the MP of the hinterland district will not get any praise from his voters, if he helped create the park at the port. Thirdly, many of the jobs created may go to immigrants from other districts or even other states. This may be because the immigrants are ready to work for less or because many locals consider a large subset of jobs beneath them. There is also the widespread practice of businesses not employing ‘locals’ because they ‘create trouble.’ Many industries in many states have the majority of labor force from out of state. Take construction in most states for example. Contractors in Kerala speak fluent Hindi because most of their labor force is from UP and Bihar.

You could argue that a MP is not the ‘leader’ of his district. That is true. In our system, the elected representatives don’t have much formal power unless they become ministers. However, what I said about MPs is applicable even to Chief Ministers (CM) to a significant extent. If a large proportion of the labor force in an industry is from outside the state, why would the CM get credit for promoting that industry? The political calculus of the Chief Minister becomes even more complicated if the industry is not well liked. For example, because it is perceived to be polluting (rightly or wrongly). Being business friendly does not help a politician win elections in India.

In spite of these negatives, there is one big reason for political leaders in India to be business friendly. The businesses may offer them money either for funding elections or for enriching themselves. Elections, and political activities in general, in India are expensive as we have covered in detail here. For instance, one estimate put the spending in 2018 assembly elections in Karnataka at Rs. 18,000 Crores! Businesses fund these expenses and politicians have to provide them services in return. Of course, many politicians keep a lot of this money for personal enrichment.

The political leadership of provinces, cities and counties in China is appointed by the China Communist Party (CCP). It is not very clear to me how the process of appointments and promotions works but it does seem that it is important for these leaders to show that they are business friendly. Leaders compete with their counterparts to increase the revenue of their cities and counties and to show development. Additionally, like their counterparts in India, the Chinese political elite also trades favors with businesses for personal enrichment. Here is Ang,

“Political elites have both career and financial incentives to enthusiastically foster development. It is often said that the promotion of local leaders is tied to economic growth but in reality, the small numbers of seats for promotion means that not all leaders may aspire to higher office. The surer incentive, therefore, is financial: the more prosperous the local economy, the more the local leaders will profit.”

‘In sum, despite the absence of electoral contests, Chinese political elites compete intensely both for economic growth and for corporate clientele for themselves.’

In both China and India, although the main reason for political leadership to be pro-business is personal enrichment, leadership in China is also required to encourage businesses. In India, voters do ask for development but this development may not be necessarily mean taking pro-business steps.

So, what does it all mean?

Discussion

The incentives for the local governments in China — at the level of political leadership, rank and file and the organization itself — are very different from those in India. I believe that this is a major reason for why China is much more welcoming of business than India. However, China’s approach is not without dangers.

As I have already discussed, linking compensation of rank-and-file officers with the revenues of the department has risks. ‘Helping hands’ can easily become ‘grabbing hands’. After all, in the story, the farmer and his wife did end up killing the Goose that laid golden eggs!

Chinese system also has a long-term risk. Unchecked promotion of business can result wasteful investment. Many China observers allege that the country has built roads that go nowhere and apartments which are never used. Here is Ang,

‘One long-term structural risk is that Chinese investors face distorted incentives to abandon productive economic activities for real estate investments, …The rush of investment towards real estate exposes the economy to speculative bubbles and over-construction, as is evident from the hordes of empty apartments across China. One study estimates that about 22 percent of Chinese urban housing is unoccupied even though the units are sold, which amounts to 50 million homes.’

While acknowledging these risks, we cannot deny that China is the global powerhouse of manufacturing and has lifted many more people out of poverty than India has. So, what can we learn from that country?

· People and systems respond to incentives. There needs to be incentives for local governments and people staffing those governments to be more welcoming of businesses.

· With GST, we have removed a key incentive for state governments to promote businesses, especially manufacturing. We should think of measures so that a state gains financially by promoting businesses.

· Our local governments have practically no stake in enabling businesses to succeed. They are usually strapped for funds too. One solution to both problems is to allow local governments to retain a small portion of the taxes that arise from businesses in their jurisdiction.

· The tying of compensation of rank-and-file bureaucracy to the revenues of the department / local government is perhaps the one thing that I found most astonishing about China. It is not a system that can be imported whole scale into India. Apart from ethical considerations, we cannot even imagine what would be the unintended consequences of such an import. I think the more basic learning is that incentives matter. They need not be monetary incentives. Maybe we can begin with measuring and evaluating key government officers differently? For example, take industrial parks. Most state development corporations follow a model where the parks sell their land or give them away from long term leases. This attracts many financial investors who have no intention of setting up an enterprise. More importantly, when the bulk of the land is sold, the park has no incentive to run it in a business-friendly manner. A business trying to expand in an existing park, has almost as much problem as a business outside the park. Small changes to how the performance of the parks is evaluated, could make them much more business friendly. I hope to cover this topic in detail in one of my future posts.

The difference in the incentive structure of governments in China and India is huge. So huge that it seems unbridgeable. And hence, there is the temptation to be resigned about the way things are. However, this need not be our reaction. First of all, we need to realize that with all its challenges, India society keeps throwing up new enterprises. The situation bad as it is, still allows the economy of the country to grow. Imagine how much better it could be if we aligned the incentives even slightly more than they are aligned today!

Author –

Yogesh Upadhyaya

(Yogesh Upadhyaya is one of the founders of AskHow India. Blogs are personal views.)

You can follow AskHow India (@AskHowIndia) or me (@Uppi89) on twitter or me on LinkedIn or Medium. DM me if you wish me to put you on WhatsApp distribution list.

______________________________

This is the second in a series on Real Ease of Doing Business. The first blog, The local bullying of business can be found here.

Thanks to Neelkanth Mishra for recommending the book ‘China’s gilded age’ and for other inputs. Thanks to Madhavan, Shankar and Ramanujam for clarifying / correcting my understanding on tax revenues for different levels of government. Opinions and errors are all mine!

Originally published on Medium